[ad_1]

Key Takeaways

Diet plays a key role in driving PCOS. Poor blood sugar regulation and chronic inflammation are the underlying causes of all symptoms.

Avoiding foods that impact these mechanisms leads to a reduction of symptoms. When replaced with more PCOS-friendly foods, you can manage PCOS symptoms long-term.

There are two steps involved in beating PCOS. Knowing which foods to avoid and what you should eat instead. You then need to know how to put these ideas into practice.

This article is all about the first step.

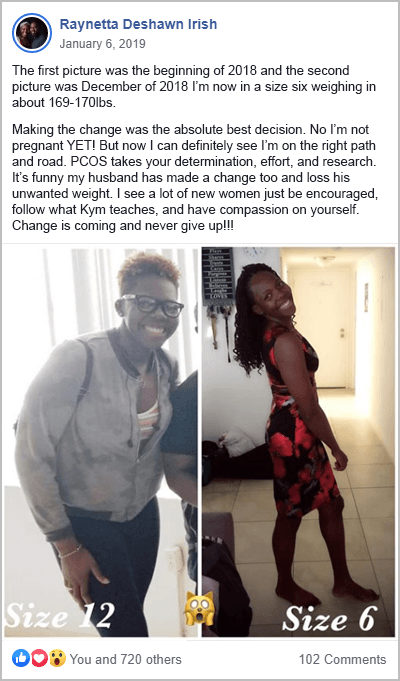

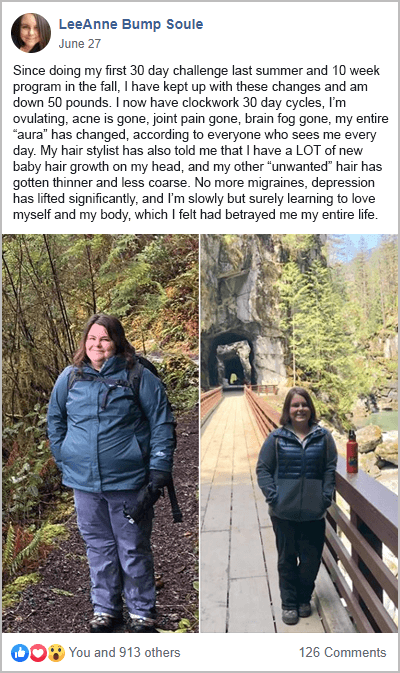

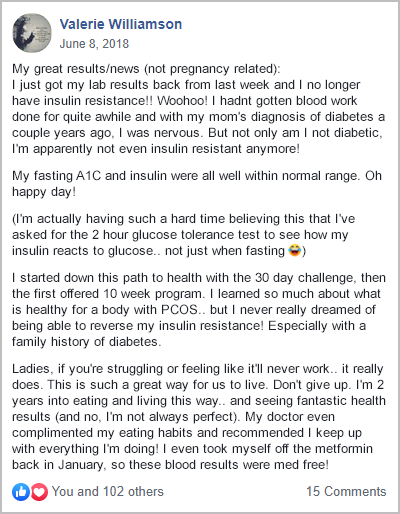

For help with both steps, join me and other like-minded women for my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. Having run this program since 2016, it’s safe to say it’s got a proven track record of getting great results. Alternatively, you can get started by downloading this free 3-Day Meal Plan.

Download a full list of common foods to avoid here.

How Diet Affects PCOS Symptoms

The relationship between diet and PCOS boils down to two mechanisms. Poor blood sugar regulation and chronic inflammation. Poor blood sugar regulation leads to insulin resistance. Chronic inflammation puts your immune system into overdrive.

These two mechanisms cause the characteristic hormonal imbalances responsible for all PCOS symptoms. This includes irregular periods, weight gain, excess hair growth, and acne. But they also result in elevated risks for cardiovascular disease. This often starts with high blood pressure and insulin resistance. The gut microbiome plays a key role in linking diet to PCOS symptoms. But the health of your microbiome is also a function of your diet.

Managing PCOS symptoms is all about how you eat. That’s why it’s important to avoid the following 13 foods.

Summary

A healthy diet can manage PCOS symptoms. The key objectives should be to improve blood sugar regulation and reduce inflammation.

1. Refined Carbohydrates

Avoiding refined carbohydrates is the best way to improve blood sugar regulation. Over time, this can improve insulin sensitivity and reverse insulin resistance.

Refined carbohydrates include things like white bread, sugary beverages, rice, pasta, and cereal. These are all highly processed foods that have had their fiber, vitamins, and minerals removed.

For a list of common refined carbohydrate foods download my free Foods to Avoid Checklist.

Summary

Refined carbohydrates are bad for blood sugar regulation.

2. Sugar

Sugar is the refined carbohydrate of all carbohydrates. This includes high fructose corn syrup, maple syrup, pasteurized honey, and fruit juice concentrate. Sugar is half made out of glucose which goes straight into your blood when you eat it. That makes blood sugar regulation tough.

But sugar is unhealthy for another reason too. Fructose.

Fructose makes up the other half of the sugar molecule. It’s known to cause inflammation [1, 2]. Excessive fructose intake deteriorates the intestinal barrier and causes endotoxemia [3]. This is where toxins in our gut leak into the bloodstream causing an immune response.

Fructose is processed by the liver. It can exacerbate insulin resistance. This is why high consumption has been linked to liver disease and [4, 5].

Cutting back on sugar is the single most important step you can take to manage PCOS. I emphasize this point in my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge.

Summary

Sugar is bad for blood sugar regulation and causes “leaky gut”. It’s also hard on the liver and causes insulin resistance.

3. Vegetable Oils

There’s a lot of confusion about what counts as unhealthy fats for PCOS.

Despite popular opinion, whole food sources of saturated fats are not unhealthy. Large studies show no difference in heart disease risk between saturated fat and polyunsaturated fat [6]. It’s well-known by scientists that government recommendations to limit saturated fats, ‘lack rigor’ [7, 8].

The unhealthy fats that you most need to be wary of are “vegetable oils”. This includes oils from soybeans, corn, rapeseed (canola), cottonseed, and safflower seeds. These oils are high in omega-6 fatty acids and low in omega-3s. That’s the opposite of what you want to maintain a healthy weight. Consumption of vegetable oils causes weight gain and obesity [9]. Imbalances in omega fats are also associated with depression, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmunity [10, 11].

Summary

Vegetable oils are the real, “bad fats”. They drive weight gain and are linked to depression, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmunity.

4. Trans-Fats

Trans fats used to be a widespread problem. These engineered vegetable oils have been linked to heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and obesity [12].

Fortunately, the FDA and other government regulators have banned these fats as a food ingredient. Australia is one of the few countries that continues to allow the inclusion of trans fats in its food products.

Until regulators catch up, Australians should check ingredient lists for trans fats. They’re labeled as “hydrogenated”, or “partially hydrogenated” vegetable oils.

Summary

Trans fats only remain a health hazard in Australia and a handful of other nations.

5. Gluten

Gluten is a group of proteins found in wheat, rye, and barley. Common gluten-containing foods include pasta, bread, breakfast cereals, and other processed foods.

Gluten is a problem for PCOS because it can cause “leaky gut syndrome” in predisposed people [13]. This is a major source of chronic inflammation. Studies have shown that gluten increases intestinal permeability even in healthy people [14].

“Predisposed people” includes those with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. There’s no evidence-based research connecting PCOS to non-celiac gluten sensitivity. But there are obvious risk factors. For example, autoimmune disorders are a predisposing factor for non-celiac gluten sensitivity [15, 16]. As explained here, PCOS is closely associated with autoimmunity.

Other risk factors include gastrointestinal disorders [17-20], eating disorders [21], food intolerances [21-23], and being female [24-26]. These are all common within the PCOS community.

The collective experience of women from my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge supports the link between PCOS and gluten. The most successful participants find that going gluten-free is an essential step in their journey.

For a list of common foods that contain gluten, download this foods to avoid checklist.

Summary

Gluten exacerbates inflammation in a large part of the PCOS community.

6. Dairy

Like gluten, there’s limited evidence linking dairy to PCOS. Reasonable arguments can be made on both sides of this debate as detailed here.

This is a situation where clinical experience is required.

From what I’ve observed as a health coach, it seems that some women with PCOS tolerate dairy better than others. But without having completed an elimination diet first, the hazards of dairy outweigh the benefits. Consuming dairy when you have a sub-clinical intolerance drives inflammation, making PCOS worse.

During my 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge, all participants go gluten and dairy-free. It’s common for participants to discover that gluten and dairy no longer agree with them.

Summary

Dairy is best excluded until an elimination diet has been completed.

7. Other Foods that Trigger Sensitivities

Like gluten and dairy, eating foods you’re sensitive to triggers an immune response. This means inflammation.

Some of the most common foods that trigger sensitivities include eggs, soy, fish, and shellfish. Different nuts and seeds are also often a problem. Some people react to nightshade vegetables like potatoes, tomatoes, eggplant, and peppers. Sulfites used as a preservative in wine and dried fruit can also cause a reaction in sensitive individuals.

Food allergy and sensitivity testing have several shortcomings. As a result, many healthcare practitioners continue to use an elimination diet as a core part of their diagnostic toolkit.

Exploring the impact of other food sensitivities makes sense after you’ve eliminated gluten and dairy.

Summary

Once dairy and gluten have been eliminated, it’s worth exploring other foods that may trigger an immune response.

8. Caffeine

Coffee and caffeine are not the same thing. Disentangling these things is important for optimizing your PCOS diet. There’s compelling evidence that the bioactive compounds in coffee are good for you [27-29]. But caffeine, in the absence of coffee, is best avoided if you have PCOS. That means energy drinks are out.

Caffeine alone reduces insulin sensitivity and raises blood glucose levels [30]. It also activates our stress response. Women with PCOS have a disturbed stress response [31]. So, drinking caffeinated beverages is likely to make you more anxious. It can also exacerbate other symptoms.

Caffeinated coffee has health benefits. But the over-activation of the stress response it may cause means it’s worth considering alternatives. Decaf gets you the best of both worlds and is an easy substitute.

Learn more about the pros and cons of coffee for PCOS here.

Summary

The bioactive compounds in coffee appear to have health benefits. But caffeine disrupts healthy insulin regulation and triggers the stress response.

9. Alcohol

From a nutritional perspective, alcohol is one of the most obvious foods to stay away from. Even rare consumption has been associated with increased rates of liver disease in women with PCOS [32].

Moderate alcohol consumption may disrupt the balance of estrogen to progesterone [33]. It’s also associated with reduced fertility [34] and is unsafe during pregnancy.

At all dosages, alcohol reduces sleep quality [35]. It’s also known to reduce self-control and increase cravings [36]. If you’re working hard on your diet or exercise habits, that can be a major problem.

But this doesn’t mean you should never drink alcohol. As I explain in my article on PCOS and alcohol, there’s still plenty of room for nuance on this subject.

Summary

Alcohol can be harmful for PCOS. It’s important to minimize the hazards of consumption.

10. Soy

Soy is one of the most confusing foods to understand from a PCOS perspective. This is because most studies looking at soy and PCOS use a single, isolated, bioactive compound. These are soy supplement studies. The results cannot be used to make informed choices about soy foods.

Any potential benefits of soy foods for PCOS rely on weak evidence. For example, a recent review investigated the role of soy on PCOS. They found “no homogenous improvement” in hormonal imbalance or fertility [37]. Many experienced healthcare practitioners believe that soy can be harmful to their PCOS patients. They recommend avoiding soy foods based on their clinical experience.

What’s much more certain is that conventionally grown soy foods are bad for PCOS. This isn’t about the soy products themselves. It’s the spray used to grow the beans. 90% of conventionally-grown soybeans are glyphosate-tolerant (GT). This enables growers to use large amounts of the herbicide, Glyphosate, to cut costs. A 2014 study found that US-grown GT soybeans contained high residues of glyphosate [38]. This is a big problem for PCOS as explained in my article on soy and PCOS.

Summary

Most evidence supporting soy for PCOS is based on isolated soy supplements. These studies are not helpful for assessing soy foods. Experienced practitioners recommend avoiding soy based on clinical experience. Herbicide use makes all conventionally-grown soy foods unsafe for PCOS.

11. Pesticide-Intensive Foods

Glyphosate isn’t the only pesticide that can harm human health. Regulators have long known that chemical pesticide exposure is linked to many chronic illnesses. This includes cancer, heart, respiratory, and neurological diseases. A large European study found 46 pesticides in the urine of adults and children [39]. At least two pesticides were present in 84% of participants [40].

Pesticide-intensive foods are especially bad for PCOS. Many pesticides are endocrine disruptors (EDCs). EDCs have been linked to insulin resistance, obesity, thyroid, and reproductive issues [41-43].

The Environmental Working Group (EWG) has identified the 12 most pesticide-intensive foods. In an ideal world, all our food would be organically grown, but these “dirty dozen” are a practical place to start.

Summary

Many common foods contain high levels of harmful pesticides. Buy organically-grown foods as far as your budget allows.

12. Processed Foods

The problem with processed foods is that they’re often high in refined carbs and sugary foods. This disrupts healthy blood sugar regulation. They also tend to contain vegetable oils, dairy, gluten, soy, and food additives. These ingredients can cause inflammation.

Fast food and fried food are the quintessential processed foods. But any product that’s been mechanically, thermally, or chemically treated is technically processed food. It’s important to understand here that it’s all about the ingredients, rather than the definition.

The ingredients used also determines the suitability of processed meats. Additive-free sausages are usually fine. But it’s best to avoid foods like ultra-processed hot dogs.

The key take-home here is that if it comes with a nutrition label, then it’s worth reading it. If you don’t like the look of the ingredients (or you don’t know what they are), then it’s a food that’s best avoided.

Summary

Processed foods generally contain many of the other foods to avoid with PCOS. Always check the ingredients list on the label.

13. FODMAPS (If You Have IBS)

Estimates suggest that around 1 in 4 women with PCOS suffer from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [44, 45]. It’s a common cause of PCOS bloating. I see this a lot within my PCOS Support Group. For these women, it’s best to avoid high-FODMAP foods.

A low FODMAP diet is difficult and intense. That’s because FODMAPS are found in many healthy everyday foods. A low FODMAP diet is generally followed for a short duration to alleviate symptoms. A reintroduction phase is then used to identify specific trigger foods. This should enable a less restrictive low FODMAP diet afterward.

Experts recommend that all patients with IBS undergo a parasite investigation. Protozoan parasites cause IBS yet this diagnosis is often missed [46, 47].

Summary

IBS is a common problem among women with PCOS. Parasitic infections are often responsible for this condition. Avoiding high FODMAP foods can help alleviate symptoms until a more long-term solution can be found.

What To Eat Instead

With all this knowledge of what not to eat with PCOS, the obvious next question is, “what should I eat instead?” The short answer is to follow these core principles:

- Eat slow-carb and low-carb, from whole food sources. A low-carb, high-fiber, low-GI diet helps stabilize blood sugar levels. This improves insulin levels and restores hormone balance. Learn more about optimizing carb intake for PCOS here.

- Consume healthy fats. Getting up to 60% of calories from whole food sources of fat is one of the best ways to improve insulin sensitivity and drive weight loss. Learn more about the best macros for PCOS here.

- Get enough protein. Adequate protein is essential for good health. But what counts as “adequate” varies with sex, age, body mass index, activity levels, and more. The USDA provides a useful online calculator for estimating an appropriate protein intake.

- Eat high-fiber foods. Especially those rich in prebiotic fibers. Doing so supports gut health, and reduces inflammation.

- Eat non-starchy vegetables. Non-starchy vegetables are rich in fiber which is good for gut health. They’re also an excellent source of vitamins, minerals, and other micronutrients.

Learn more about a PCOS Diet here, and download my PCOS Diet Cheat Sheet.

Summary

A healthy PCOS diet is all about eating nutrient-dense whole foods that support better blood sugar regulation. You also want to consume foods that improve gut health and reduce inflammation.

The Bottom Line

PCOS is driven by poor blood sugar regulation and chronic inflammation. Both of these mechanisms are dialed up or down by the foods we eat. Because of this, dietary change is a powerful intervention for reducing the full scope of PCOS-related symptoms.

The most obvious foods to avoid with PCOS are refined carbs, sugar, vegetable oils, trans-fats, and highly-processed foods. Doing an elimination diet to determine your sensitivity to gluten, dairy, and other foods is also critical. Women with PCOS should be strategic about how they approach caffeinated drinks and alcohol. Soy and other pesticide-intensive foods are best avoided. For PCOS women with IBS, a low FODMAP diet should be followed until a better long-term solution can be found.

If you’re ready to embrace a PCOS diet today and avoid these foods, then sign-up now for my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. You can also get started with this free 3-Day Meal Plan.

Author

Combining rigorous science and clinical advice with a pragmatic approach to habit change, Kym is on a mission to show women with PCOS how to take back control of their health and fertility. Read more about Kym and her team here.

Co-Authors

This blog post has been critically reviewed to ensure accurate interpretation and presentation of the scientific literature by Dr. Jessica A McCoy, Ph.D. Dr McCoy has a master’s degree in cellular and molecular biology, and a doctorate in reproductive biology and environmental health. She currently serves as a University professor at the College of Charleston, South Carolina.

This blog post has also been medically reviewed and approved by Dr. Sarah Lee, M.D. Dr. Lee is a board-certified Physician practicing with Intermountain Healthcare in Utah. She obtained a Bachelor of Science in Biology from the University of Texas at Austin before earning her Doctor of Medicine from UT Health San Antonio.

References

1DiNicolantonio, J.J., et al., Fructose-induced inflammation and increased cortisol: A new mechanism for how sugar induces visceral adiposity. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 2018. 61(1): p. 3-9.

2Jones, N., et al., Fructose reprogrammes glutamine-dependent oxidative metabolism to support LPS-induced inflammation. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 1209.

3Todoric, J., et al., Fructose stimulated de novo lipogenesis is promoted by inflammation. Nat Metab, 2020. 2(10): p. 1034-1045.

4Jensen, T., et al., Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol, 2018. 68(5): p. 1063-1075.

5Dornas, W.C., et al., Health implications of high-fructose intake and current research. Adv Nutr, 2015. 6(6): p. 729-37.

6Hamley, S., The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr J, 2017. 16(1): p. 30.

7Astrup, A., et al., Dietary Saturated Fats and Health: Are the U.S. Guidelines Evidence-Based? Nutrients, 2021. 13(10).

8Hite, A.H., et al., In the face of contradictory evidence: report of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committee. Nutrition, 2010. 26(10): p. 915-24.

9Simopoulos, A.P., An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity. Nutrients, 2016. 8(3): p. 128.

10Sanhueza, C., L. Ryan, and D.R. Foxcroft, Diet and the risk of unipolar depression in adults: systematic review of cohort studies. J Hum Nutr Diet, 2013. 26(1): p. 56-70.

11Fernandes, G., et al., Effects of n-3 fatty acids on autoimmunity and osteoporosis. Front Biosci, 2008. 13: p. 4015-20.

12Mozaffarian, D., A. Aro, and W.C. Willett, Health effects of trans-fatty acids: experimental and observational evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2009. 63 Suppl 2: p. S5-21.

13Caio, G., et al., Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Gut Microbiota Composition in Patients with Celiac Disease and Non-Celiac Gluten/Wheat Sensitivity. Nutrients, 2020. 12(6).

14Hollon, J., et al., Effect of gliadin on permeability of intestinal biopsy explants from celiac disease patients and patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Nutrients, 2015. 7(3): p. 1565-76.

15Carroccio, A., et al., High Proportions of People With Nonceliac Wheat Sensitivity Have Autoimmune Disease or Antinuclear Antibodies. Gastroenterology, 2015. 149(3): p. 596-603.e1.

16Mansueto, P., et al., Autoimmunity Features in Patients With Non-Celiac Wheat Sensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol, 2021. 116(5): p. 1015-1023.

17Sapone, A., et al., Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Med, 2011. 9: p. 23.

18Catassi, C., et al., The Overlapping Area of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS) and Wheat-Sensitive Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): An Update. Nutrients, 2017. 9(11).

19Shahbazkhani, B., et al., Prevalence of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in Patients with Refractory Functional Dyspepsia: a Randomized Double-blind Placebo Controlled Trial. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 2401.

20Barbaro, M.R., et al., Recent advances in understanding non-celiac gluten sensitivity. F1000Res, 2018. 7.

21Gadelha de Mattos, Y.A., et al., Self-Reported Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in Brazil: Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of Italian Questionnaire. Nutrients, 2019. 11(4).

22Carroccio, A., et al., Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012. 107(12): p. 1898-906; quiz 1907.

23Carroccio, A., et al., Duodenal and Rectal Mucosa Inflammation in Patients With Non-celiac Wheat Sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019. 17(4): p. 682-690.e3.

24Volta, U., et al., An Italian prospective multicenter survey on patients suspected of having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Med, 2014. 12: p. 85.

25van Gils, T., et al., Prevalence and Characterization of Self-Reported Gluten Sensitivity in The Netherlands. Nutrients, 2016. 8(11).

26Zanini, B., et al., Duodenal histological features in suspected non-celiac gluten sensitivity: new insights into a still undefined condition. Virchows Arch, 2018. 473(2): p. 229-234.

27Ding, M., et al., Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, 2014. 37(2): p. 569-86.

28Jiang, X., D. Zhang, and W. Jiang, Coffee and caffeine intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr, 2014. 53(1): p. 25-38.

29Poole, R., et al., Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. Bmj, 2017. 359: p. j5024.

30Emami, M.R., et al., Acute effects of caffeine ingestion on glycemic indices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Complement Ther Med, 2019. 44: p. 282-290.

31Benson, S., et al., Disturbed stress responses in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2009. 34(5): p. 727-35.

32Hossain, N., et al., Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Scand J Gastroenterol, 2011. 46(4): p. 479-84.

33Gill, J., The effects of moderate alcohol consumption on female hormone levels and reproductive function. Alcohol Alcohol, 2000. 35(5): p. 417-23.

34Anwar, M.Y., M. Marcus, and K.C. Taylor, The association between alcohol intake and fecundability during menstrual cycle phases. Hum Reprod, 2021. 36(9): p. 2538-2548.

35Ebrahim, I.O., et al., Alcohol and sleep I: effects on normal sleep. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2013. 37(4): p. 539-49.

36Remmerswaal, D., et al., Impaired subjective self-control in alcohol use: An ecological momentary assessment study. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2019. 204: p. 107479.

37Rizzo, G., et al., The role of soy and soy isoflavones on women’s fertility and related outcomes: an update. J Nutr Sci, 2022. 11: p. e17.

38Bøhn, T., et al., Compositional differences in soybeans on the market: glyphosate accumulates in Roundup Ready GM soybeans. Food Chem, 2014. 153: p. 207-15.

39Huber, C., et al., A large scale multi-laboratory suspect screening of pesticide metabolites in human biomonitoring: From tentative annotations to verified occurrences. Environ Int, 2022. 168: p. 107452.

40Ottenbros, I., et al., Assessment of exposure to pesticide mixtures in five European countries by a harmonized urinary suspect screening approach. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2023. 248: p. 114105.

41De Coster, S. and N. van Larebeke, Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: associated disorders and mechanisms of action. J Environ Public Health, 2012. 2012: p. 713696.

42Gore, A.C., et al., EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Rev, 2015. 36(6): p. E1-e150.

43Janesick, A.S. and B. Blumberg, Obesogens: an emerging threat to public health. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2016. 214(5): p. 559-65.

44Cañón, M., et al., Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and health-related quality of life in adults aged 18 to 30 years in a Colombian University: an electronic survey. Ann Gastroenterol, 2017. 30(1): p. 67-75.

45Kałużna, M., et al., Are patients with polycystic ovary syndrome more prone to irritable bowel syndrome? Endocr Connect, 2022. 11(4).

46Stark, D., et al., Irritable bowel syndrome: a review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis. Int J Parasitol, 2007. 37(1): p. 11-20.

47Yakoob, J., et al., Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis in patients fulfilling irritable bowel syndrome criteria. Parasitol Res, 2010. 107(3): p. 679-84.

Combining rigorous science and clinical advice with a pragmatic approach to habit change, Kym is on a mission to show women with PCOS how to take back control of their health and fertility. Read more about Kym and her team here.

Co-Authors

This blog post has been critically reviewed to ensure accurate interpretation and presentation of the scientific literature by Dr. Jessica A McCoy, Ph.D. Dr McCoy has a master’s degree in cellular and molecular biology, and a doctorate in reproductive biology and environmental health. She currently serves as a University professor at the College of Charleston, South Carolina.

This blog post has also been medically reviewed and approved by Dr. Sarah Lee, M.D. Dr. Lee is a board-certified Physician practicing with Intermountain Healthcare in Utah. She obtained a Bachelor of Science in Biology from the University of Texas at Austin before earning her Doctor of Medicine from UT Health San Antonio.

[ad_2]

Source link